I. Background and Methods

Laboratory usability testing – where a small group of users are brought into a lab and prompted to complete tasks while under observation from researchers – is an extremely tool for designers and researchers. It can also be extremely expensive, time-consuming, and a lot of trouble to schedule. What if it could be simplified?

Researchers Thomas Tullis, Stan Fleischman, Michelle McNulty, Carrie Cianchette, and Margerite Bergel conducted a study comparing lab testing (where users are brought into the lab) with remote usability testing [warning: download link to PDF]. The product being studied was a company HR website, and users were asked to complete certain tasks (like figuring out how to have $200 deposited automatically every month from one’s salary into a savings account).

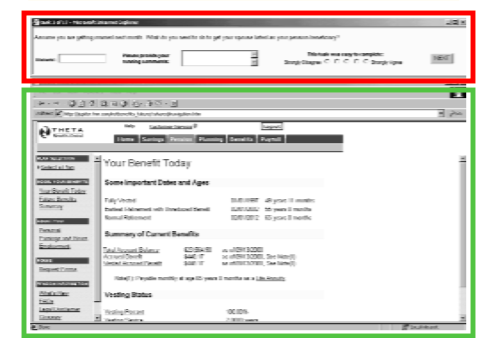

Instead of having researchers on hand to collect data, the remote tests captured the user’s clicks and activity. The test also involved providing remote users with a small browser window open on the top of their computer screen so that users could give comments and feedback as the test progressed. The embedded image below shows how this looks.

The green box indicates the website’ content, while the red box indicates the small browser window that participants use to give feedback and comments.

II. Results

29 users completed a remote test, while 8 users participated in lab testing. The two tests found no significant differences in task completion rates or average task duration time. Researchers asked participants from both groups about their subjective opinions on the website, and remote participants seemed to be harsher critics than lab participants. Remote participants gave more negative opinions on all but one of the 9 questions asked.

The authors have two possible explanations for this. The first is that it could be an artifact of the small sample sizes (29 v. 8). The second is that participants often feel badly when criticizing a product being tested, even if the people doing the testing didn’t create the product. The authors point mention that in their experience, some participants who are explicitly told that the testers are not the site designers still seem hesitant to offer criticism.

This is a valid point, and it could very well have been the problem. But the researchers conducted a second experiment that didn’t replicate the same pattern, and in fact found very little correlation between in-lab testing and remote testing. This makes sample sizes seem like a more likely culprit. Again, task performance and task data was roughly identical between the two different types of testing, and the authors conclude that quantitative data collected via remote testing is likely to be robust and reliable.

III. The (semi) bad news

The first experiment found that the 8 lab users identified 26 usability problems with the web site, while remote participants only identified 16 problems. 11 of those issues overlapped, 5 were identified only via remote testing, and 15 were found only via lab testing. Because identifying usability problems is one of the key goals of usability testing, this seems like a bad sign for remote testing.

But the authors’ second experiment involved a much larger sample size of remote testers (88 remote participants compared to 8 lab participants). In this experiment, the lab test identified 9 usability issues while the remote test identified 17, while 7 of the issues overlapped. The researchers conclude that this is likely a function of the large sample size: more participants means more opportunities to identify usability problems.

For researchers who are tempted to do away with cumbersome usability testing in favor of lightweight remote testing, these are interesting but mixed results. It seems that remote testing can sometimes do better than lab testing, but it usually requires larger sample sizes (sometimes much larger). And, unfortunately, the sample size at which a remote test can safely be assumed to be equivalent to a usability test is still nebulous. This study implies that for websites, this magic sample size is larger than 30 but smaller than 90, but beyond that we can’t really be sure.

These are positive results for remote testing, but they are cautiously positive rather than overwhelmingly positive. To my eye, they seem to indicate that remote testing is reliable for quantitative metrics and that it might potentially work as a substitute for lab testing if the sample size is large enough. But they also indicate that remote testing will often work better as a supplement to traditional user testing rather totally usurping it.

UX takeaways.

- Face-to-face testing and remote testing might introduce different types of bias. For example, participants might be more likely to give positive answers during lab testing than during remote testing. Future research will hopefully examine this particular area in more depth.

- Some percentage of remote users usually end up abandoning the survey before completion. This could bias the results, which researchers should consider if they are relying on a highly representative sample of users. For example is that users with less experience in a certain product domain might be less likely to finish a long remote usability test involving that product than users who have experience in that domain. This seems less likely to be a problem with laboratory testing where abandoning a session is much more complicated and consequently much rarer.

- The sample size for lab testing is usually small enough that any quantitative data they produce (like subjective assessment data) is unlikely to be very robust.

- Remote testing and lab testing often identify similar usability problems, but both methods often identify usability issues that the other did not find. This implies that the two methods of testing would supplement each other well for researchers trying to find an exhaustive list of usability issues.